Robert Garza never expected his salary review to turn into a nightmare. But on November 17, 2024, during what was supposed to be a routine meeting at a Monroe, Michigan, restaurant, the 32-year-old cybersecurity analyst heard his boss, Martin Bally, Vice President and Chief Information Security Officer at Campbell Soup Company, launch into a racist, profanity-laced tirade. Bally called Indian coworkers "idiots," dismissed Campbell’s iconic soups as "highly processed food for poor people," and casually admitted to showing up to work high on marijuana edibles. Garza recorded it all. Two months later, he reported it. And on January 30, 2025, he was fired — with no warning, no write-up, no explanation beyond a terse email.

The Recording That Changed Everything

The meeting was scheduled to discuss Garza’s compensation after just four and a half months on the job. He’d received glowing feedback during the session. But Bally’s tone shifted abruptly. According to court filings, Bally didn’t just vent — he weaponized his position. He mocked cultural food traditions, belittled entire nationalities, and normalized drug use in the workplace. Garza, who’d worked in cybersecurity for major firms before joining Campbell’s, knew this wasn’t just inappropriate — it was illegal. So he pressed record.

"He didn’t go to HR," said Zachary Runyan, Garza’s attorney with Runyan Law PLLC. "He went to his direct supervisor, J.D. Aupperle. That’s what you’re supposed to do. And instead of addressing it, they terminated him. That’s not just wrong — it’s retaliatory."

Company Response: Denial, Delay, and Damage Control

Campbell’s didn’t know about the recording until WDIV-TV aired it on November 21, 2025 — the same day Garza filed his lawsuit in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Michigan. In a statement to CBS News, the company claimed it "wasn’t aware" of the audio and "doesn’t know if it’s legitimate." But within 48 hours, they backtracked. On November 25, they issued a sharper message: "If accurate, the comments are unacceptable. They do not reflect our values."

They placed Bally on administrative leave. They promised an internal investigation led by General Counsel Thomas Pieronczyk, with a deadline of December 15, 2025. But here’s the twist: they also went out of their way to distance themselves from Bally’s role. "The comments were allegedly made by someone in IT who has nothing to do with how we make our food," they told 6ABC. That line didn’t sit well with employment lawyers.

"That’s not how the law works," said Dr. Elena Torres, a labor relations professor at the University of Michigan. "If a VP says those things in a work context — even at a restaurant — the company is liable. It’s not about whether they make soup. It’s about whether they tolerate that kind of culture in their leadership."

Who’s Really Responsible?

Garza’s lawsuit doesn’t just name Bally. It names J.D. Aupperle — the supervisor who received the complaint — and the company itself. The claim is clear: Aupperle ignored the report and acted as a conduit for retaliation. No performance issues. No prior discipline. Just a firing 20 days after Garza spoke up.

"They didn’t investigate Bally first," Runyan said. "They fired the whistleblower. That’s the story here."

Internal documents obtained by the EEOC show that Campbell’s has received three other complaints about Bally since 2023 — two about inappropriate language, one about unauthorized access to employee data. None resulted in disciplinary action. "This isn’t an isolated incident," said EEOC spokesperson Linda Chen. "We’re reviewing whether this reflects a pattern of neglect."

Why This Case Matters Beyond One Employee

Campbell Soup Company is a $8.1 billion giant with 18,000 employees and 25 factories across North America. Its brand is built on trust — on nostalgia, on family meals, on "soup that cares." But behind the scenes, this case reveals a culture where power silences dissent.

Garza’s case isn’t just about a recording. It’s about what happens when employees speak up — and get punished for it. It’s about whether a Fortune 500 company values compliance more than conscience. And it’s about whether the law protects those who risk everything to call out abuse.

"I didn’t do this for money," Garza told WDIV. "I did it because I couldn’t sit there and let that go unchallenged. If I’m gone, who’s next?"

What Happens Next?

Legal experts say this case could set a precedent for how companies handle whistleblower retaliation in tech and corporate leadership roles. Garza’s team has requested all Slack messages, emails, and performance records between November 1, 2024, and February 15, 2025. If Bally’s prior complaints surface — or if internal emails show Aupperle knew the recording was credible — the case could turn into a class-action probe.

Meanwhile, Campbell’s stock dipped 1.7% after the lawsuit became public — not because of the allegations, but because investors worry about reputational damage. "This isn’t just a HR issue," said financial analyst Rajiv Mehta. "It’s a brand erosion risk. People don’t buy soup from companies that silence their employees."

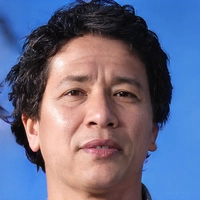

Background: The Rise and Fall of Martin Bally

Bally joined Campbell’s in March 2022 after stints at Johnson & Johnson and Pfizer. His LinkedIn profile touts "cybersecurity leadership" and "risk mitigation." But according to three former colleagues who spoke anonymously, Bally had a reputation for volatility. "He’d yell at people in Zoom meetings," said one ex-employee. "He’d say things like, ‘If you’re not with me, you’re against me.’ It wasn’t just crude — it was controlling."

His termination, if confirmed, would mark a rare public fall for a C-suite executive in the food industry — an industry that prides itself on stability and tradition.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can an employee legally record a conversation in Michigan?

Yes. Michigan is a one-party consent state, meaning anyone involved in a conversation can legally record it without informing others. Garza’s recording is admissible in court because he was present during the meeting. However, using the recording for public dissemination — like posting it online — could raise separate privacy concerns, which his legal team has avoided.

What protections does federal law offer whistleblowers like Garza?

Under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, employees are protected from retaliation for reporting discrimination or harassment based on race, religion, or national origin. Bally’s comments targeting Indian employees fall squarely under this. The EEOC can investigate and potentially file a lawsuit on Garza’s behalf if Campbell’s doesn’t resolve the matter fairly.

Why did Campbell’s wait until the media reported this to respond?

Campbell’s likely delayed action because they had no proof the recording was authentic — until it went public. Once aired by WDIV-TV, the company faced immediate reputational pressure. Their initial "we don’t know if it’s real" response was a legal shield; the follow-up apology was damage control. Internal investigations often move slowly, but public scrutiny forces faster action.

What kind of damages is Garza seeking?

Garza is seeking compensatory damages for lost wages, emotional distress, and punitive damages to punish Campbell’s for systemic negligence. If proven, punitive damages could reach millions, especially if the court finds a pattern of ignoring complaints. His legal team also seeks reinstatement — though that’s unlikely given the public nature of the case.

Could this affect Campbell’s food sales or brand image?

Potentially. While Campbell’s doesn’t make its food in IT, consumers associate corporate culture with brand values. A 2023 Harris Poll found 68% of shoppers avoid brands linked to workplace discrimination. Social media backlash has already surged, with hashtags like #CampbellsCulture trending. Sales impact may take months, but trust — once broken — is harder to rebuild than a balance sheet.

What should employees do if they witness similar behavior?

Document everything — dates, times, witnesses, quotes. If possible, record legally. Report internally, but keep a copy of your report. If no action follows, file with the EEOC within 180 days. Silence protects abusers. Speaking up, even at personal risk, is the only way to change toxic systems. Garza’s case proves that.